December 1, 2025 | 4.5 Minute Read

Imagine locking in a super-low mortgage rate—2% or 3%—for 30 years… and being able to take that same loan with you when you move to a new house. Sounds awesome, right? That’s the basic idea behind portable mortgages, a concept the government is now exploring as a way to unlock the housing market and improve affordability.

But the big questions are: Would portable mortgages actually work in the U.S.? How realistic are they? And who would benefit?

We’re breaking it all down.

Housing affordability has exploded into national conversation over the last few weeks. For those of us who are real estate investors, operators, and industry professionals, this problem isn’t new—but now the broader public and policymakers are paying attention.

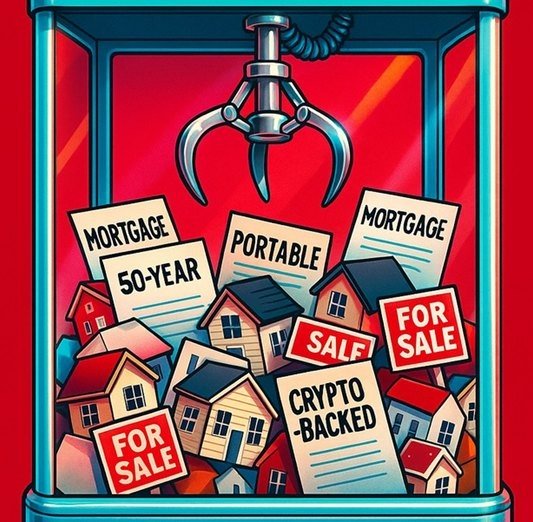

A few weeks ago the administration floated the idea of a 50-year mortgage. Reaction from the industry was lukewarm at best, and most experts agree it’s unlikely to meaningfully boost affordability or unfreeze the housing market.

So now there’s a new proposal on the table: portable mortgages.

If you’re not familiar with portability, it’s a feature used in places like Canada, the U.K., and New Zealand. Homeowners there can take their existing mortgage—along with its interest rate—to their next home.

Picture this: you locked in an amazing 2–3% rate during COVID. A few years later, you want to move. With a portable mortgage, instead of paying off your old loan and taking out a new one at 6.5% or higher, you simply bring your old loan with you.

It’s a hugely appealing idea for homeowners. In theory, it could reduce the lock-in effect, boost sales volume, and even help affordability.

But how would it actually work? Could U.S. lenders realistically offer this? And would it solve the problems people hope it will?

What a portable mortgage is (and isn’t)

A portable mortgage allows you to take your existing loan with you when you sell one home and buy another. Instead of paying off the loan and starting over, the mortgage essentially “travels” with you—the borrower—rather than staying tied to the original property.

Of course, it’s not magic. If you’re moving from a $300,000 house to a $500,000 house, you can’t just transfer your existing loan balance and low rate to the new property. In countries where portability exists, lenders use a structure called “blend and extend.”

Example:

You owe $250,000 at 3% on your current home.

You need an additional $150,000 to buy the next home.

With portability, you keep that $250k at 3%, and you borrow the additional $150k at the current market rate. Your final rate is blended between the two. The loan term usually restarts as well, meaning you’ll begin a new amortization schedule with a higher proportion of interest.

That’s how it works in theory.

How portability works in countries that already use it

But let’s look at how it works in the real world—specifically in Canada.

Despite all the talk online about “just doing what Canada does,” the Canadian system is nothing like the U.S. system. Their portable mortgages are usually:

5-year fixed terms (not 30-year)

Loaded with prepayment penalties

Structured as optional products lenders may offer

These distinctions matter. Canadian mortgages are shorter, more expensive to break, and much more flexible for lenders—not borrowers.

The entire system is built around different assumptions, different capital markets, and different risk structures.

Why the U.S. mortgage system doesn’t currently allow it

So why doesn’t the U.S. have portability? And could we?

To answer that, we need to look at how the U.S. mortgage system actually works—because it’s very different from almost every other country.

Most U.S. mortgages are underwritten to strict standards so they can be sold to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Ginnie Mae. Those loans are then bundled into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and sold to investors—pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and more.

This entire system depends on predictability. The loan must be tied to a specific piece of collateral (the property). The repayment schedule must be fixed. Expected prepayment timelines—usually 7–10 years—are built into the pricing.

That’s why U.S. mortgage rates are lower than almost anywhere else in the world.

It’s also why we have the 30-year fixed mortgage—something very few countries offer.

Now imagine inserting portability into that system.

As soon as you detach the mortgage from the property, you break the known collateral, the expected repayment timeline, and the predictability investors rely on. A lender who expected to be paid off in 7–10 years could suddenly be stuck with a 3% loan for 20 or 25 years.

That unpredictability would ripple through the entire MBS market.

And when uncertainty goes up… so do interest rates.

Whether it’s even feasible to implement

Now let’s shift perspectives.

Forget borrowers for a moment—think like a lender.

If you made a loan at 3% in 2021 and rates are now 6–7%, would you voluntarily let a borrower keep that 3% rate for another decade or more? Absolutely not. You’d want that loan paid off so you could re-lend at today’s higher rates.

There is zero economic incentive for lenders to allow portability on existing mortgages.

The only way it could happen is if the government paid lenders to do it—and if we’re going to invest billions to improve affordability, there are far better places to put that money than subsidizing banks.

So here’s my take:

Portable mortgages for existing loans are extremely unlikely.

It would require massive, expensive government intervention.

It doesn’t meaningfully help first-time buyers—only existing homeowners.

It risks destabilizing the MBS market and raising mortgage rates.

Could lenders offer portable mortgages for new loans going forward?

Yes, maybe. A few might try it. But expect:

shorter terms

prepayment penalties

higher rates

In other words—something that looks a lot like the Canadian model.

Useful for some people, maybe. A game-changer for affordability? Not even close.

If I had to choose between a Canadian-style portable mortgage and the 30-year fixed-rate U.S. mortgage we already have, I’d stick with the 30-year fixed every time—especially as an investor.